The River Nile divides Luxor, with the West Bank and the East Bank holding different roles in ancient Egyptian beliefs and society. The West Bank was thought to symbolise Death, and the East Bank, Life. Therefore, all of the tombs and mortuary temples in Egypt are found on the western side of the Nile, and all of the temples (as the homes of the gods) are found on the east.

As with all the ancient sites in Egypt, there is simply so much to see and take in. I can not recommend getting a guide enough, as you will learn so much more about these iconic tombs. But hopefully, this reference guide will give you just a little bit of context to get you started in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens. Check out my similar guide to the temples of Upper Egypt to find out more about the context in which the ancient Egyptians created these wonders.

DEATH IN ANCIENT EGYPT

During the Old and Middle Kingdoms, most pharaohs were buried in pyramids. However, these were frequently robbed – and being a huge edifice sitting in the desert, were not exactly easy to hide the location of! At the start of the New Kingdom, the rulers of Egypt attempted to take a stealthier approach. Burials moved to tombs cut deep into a valley located across the river from the ancient city of Thebes on the west bank of the Nile. Snappily titled “The Great and Majestic Necropolis of the Millions of Years of the Pharaoh, Life, Strength, Health in The West of Thebes”, this would have been a great plan… were it not for the many, many workmen, priests and others involved in the creation of each tomb. Although the location of the royal necropolis was a widely known “secret”, the pharaohs still did their best to hide the entrances to their burial sites in the hope of protecting their tombs from thieves. Unfortunately, this was not to be successful. Eventually, every tomb – with the exception of one rather famous one! – was robbed and looted of its treasure at some point in ancient antiquity.

THE EGYPTIAN SOUL

The Egyptians viewed the ‘soul’ as a complex, multifaceted entity. Each person had both a ka and a ba. The ka was the life force. Under normal circumstances, the ka departed at death. But an individual’s ka could be sustained after death thanks to offerings left in his or her tomb.

The ba was a person’s individual essence. It was depicted as a human-headed bird. The main goal after death was to unite the ka with the ba, forming what’s known as akh. By accomplishing this, unity with the gods could be achieved. Mummification, funerary rites and tomb artwork were all intended to help facilitate this spiritual process.

FUNERARY RITES

A person’s body was the home of his ba during life. The mummy was intended as a receptacle for the ba after death. This gave the deceased unlimited time to work on merging their ba and ka together in the spirit realms.

By the New Kingdom, the Egyptians had mastered the art of mummification, and many mummies remain perfectly intact today. Specialised workers would have been trained in mummification, working at embalming houses throughout the country. In total, each mummy took around 70 days to complete.

The first step was the removal of the brain. A rod was inserted through the nostrils and the brain extracted through the nose. The skull was then filled with resins to slow decomposition. Next, an incision was made to remove the organs, which were placed in canopic jars. Typically made of alabaster, the jars represented the four sons of Horus. The body was then sterilized, dehydrated and coated with molten resin.

For those interested in mummification, there’s a Mummification Museum in Luxor not far from the Luxor Museum. It is included in the Luxor Pass or costs £100EGP for an adult ticket.

THE FUNERARY TEXTS

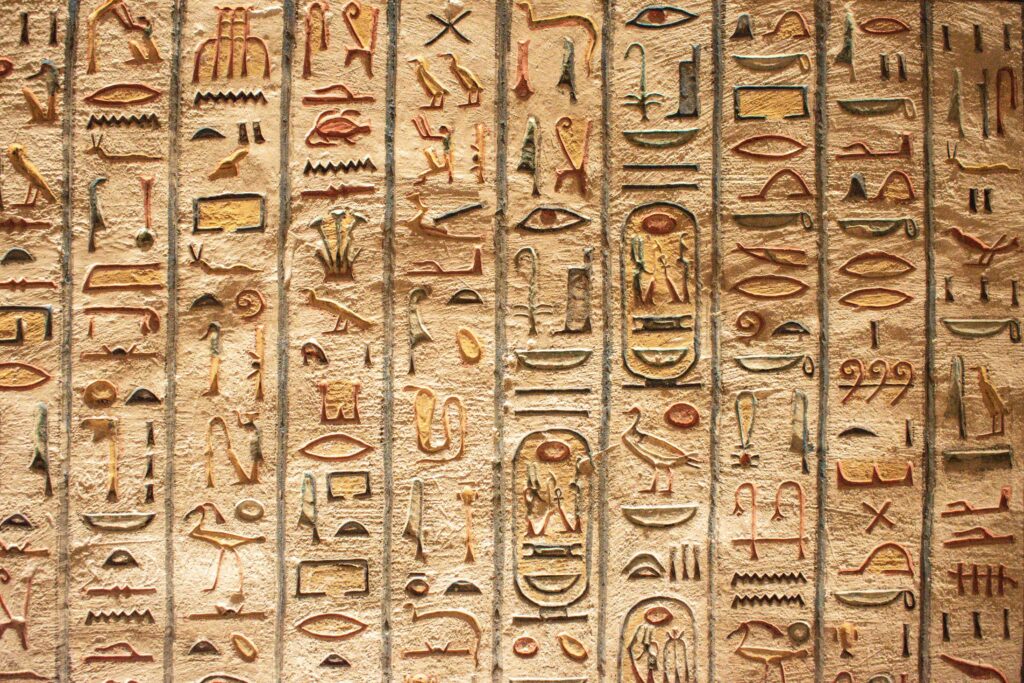

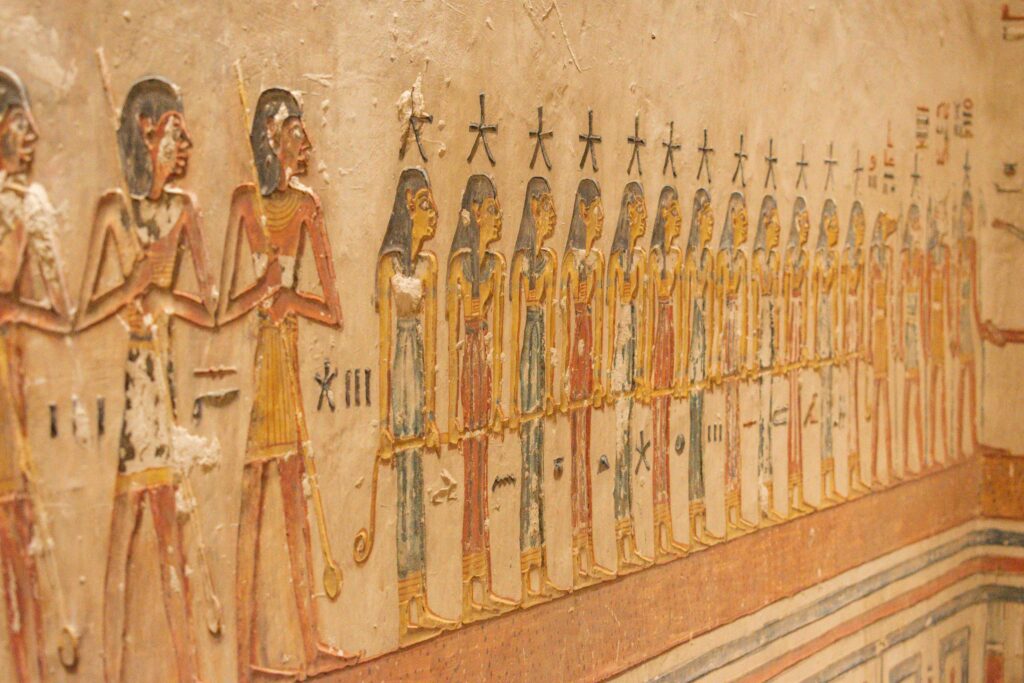

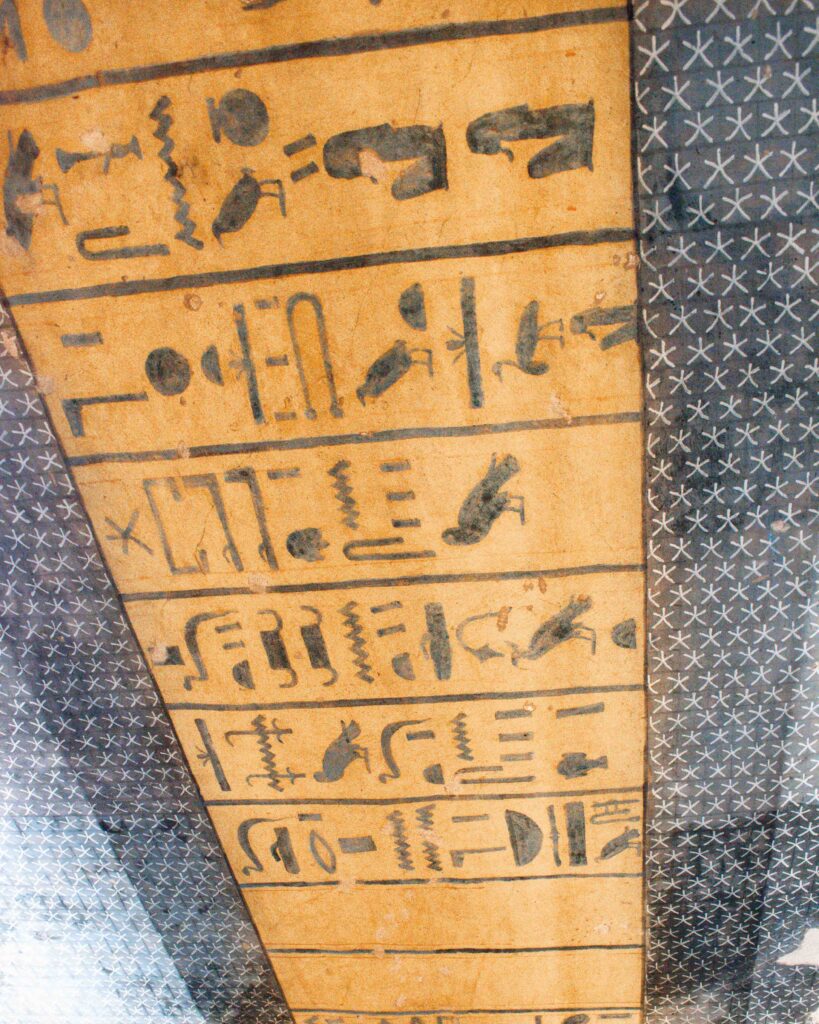

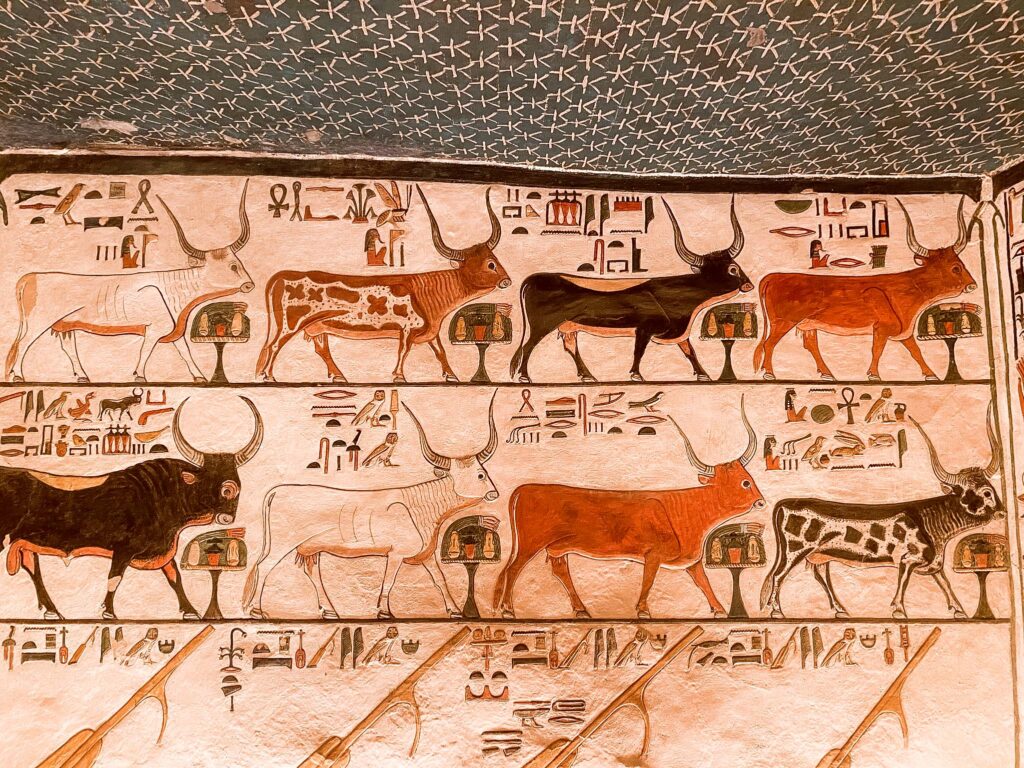

The artwork covering the tombs was intended for the soul of the deceased.

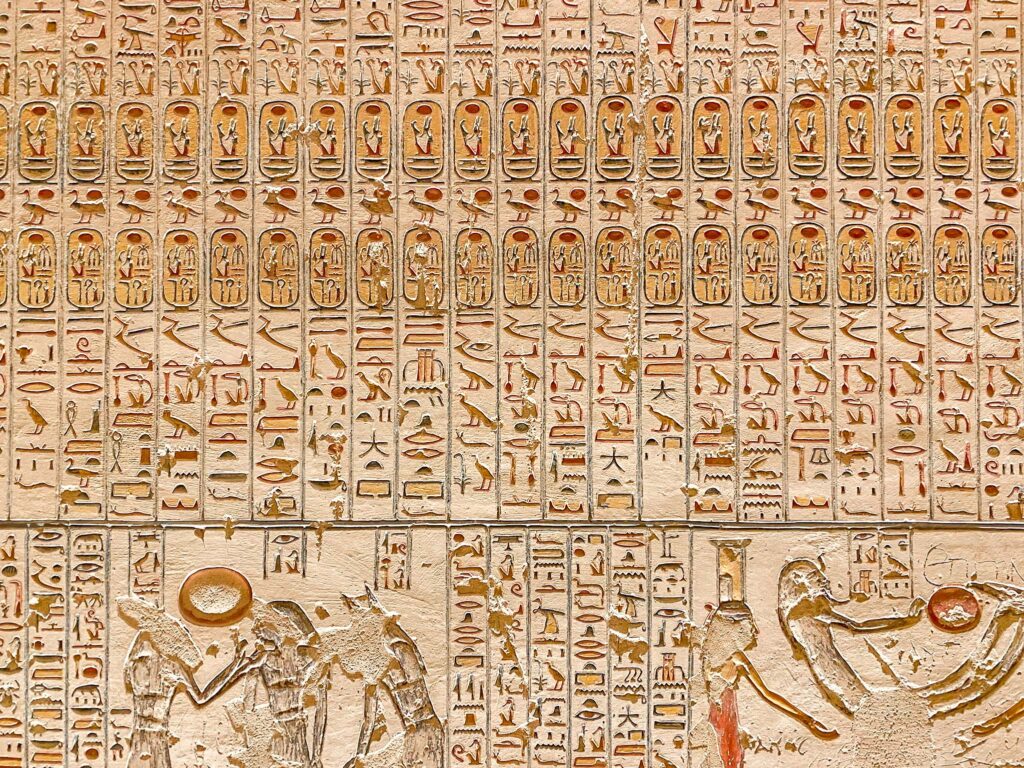

During the New Kingdom, numerous funerary texts were created, derived from the much more ancient Pyramid Texts (so called as they first appeared in the pyramids of the late 5th and 6th Dynasties, though they likely existed in oral form long before that). They all represent the journey which the soul of the dead must take in the duat, or underworld.

In death, a pharaoh identified with Osiris, lord of the underworld. With the help of various deities, he must overcome obstacles, put in place by the great adversary, Set. The ultimate goal is to overcome these challenges, to identify with Horus and ascend to the heavens. There, the pharaoh becomes one with Ra for eternity.

One of the main texts depicted throughout the royal tombs is the Am Duat, which details the journey of the king’s soul throughout the twelve hours of night. The Book of Gates is a similar text but deals with gates or portals over the individual hours.

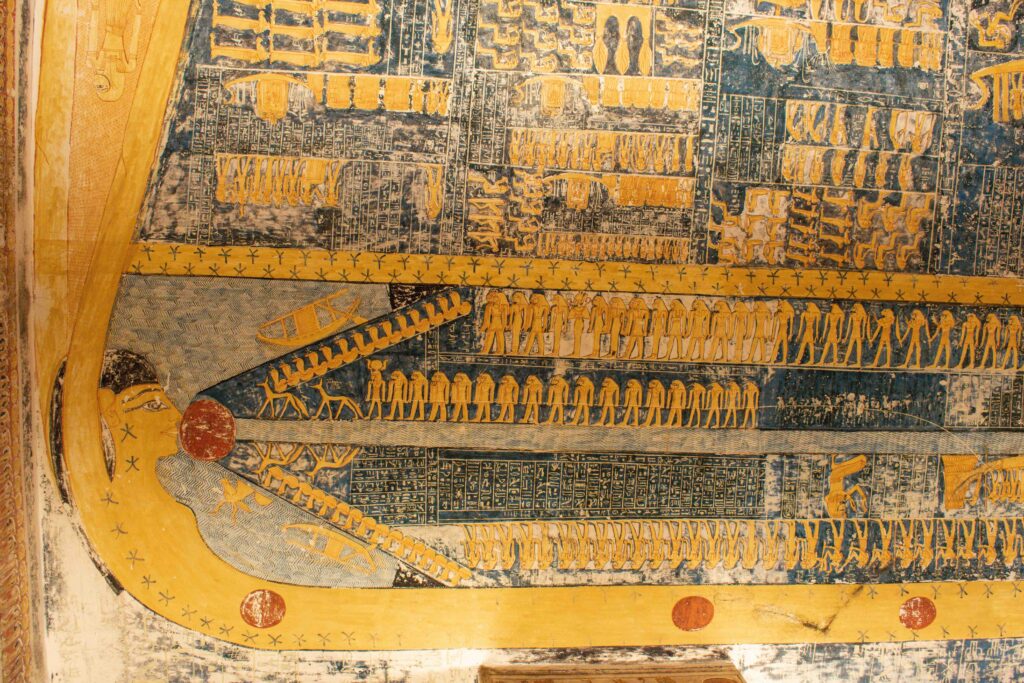

The Book of Caverns focuses on the punishments waiting for the enemies of Osiris. The Book of the Day and the Book of the Night show the sun passing through Nut, the sky goddess. These are often depicted on ceilings.

At nearly every tomb entrance, the Litany of Ra is shown. The text lists the 75 different names of Ra.

THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS

To date, 63 tombs have been discovered in the Valley of the Kings, the burial places of dozens of pharaohs, a few of their sons and even some high ranking officials. Each tomb is numbered by the “KV” designation – short for Kings Valley. Due to the strain that visitor numbers put on the tombs, only a small selection of tombs are open to visit each day. The admission ticket allows access to three tombs. If you would like to visit more, you must purchase an additional ticket, which will allow you into an additional three tombs. The Tombs of Rameses V/VI, Seti I and Tutankhamen each require a separate, additional ticket. We visited 4 tombs in total. The other tombs that may be open during your visit, are those of Ay, Seti II, Siptah, Twosret/Setnakht, Ramesses IV and Ramesses VII.

RAMSSES V & VI (KV9)

Ramesses V took the throne in 1147 BCE. His reign was destined to be short – only four years – and was beset by financial problems and Libyan raiding parties. In 1143 BCE he contracted the first documented case of small pox which brought about a quick end to his brief reign.

After his death Ramesses V’s paternal uncle assumed the throne and was crowned Ramesses VI. He reigned for the next 8 years (1143–1136 BCE).

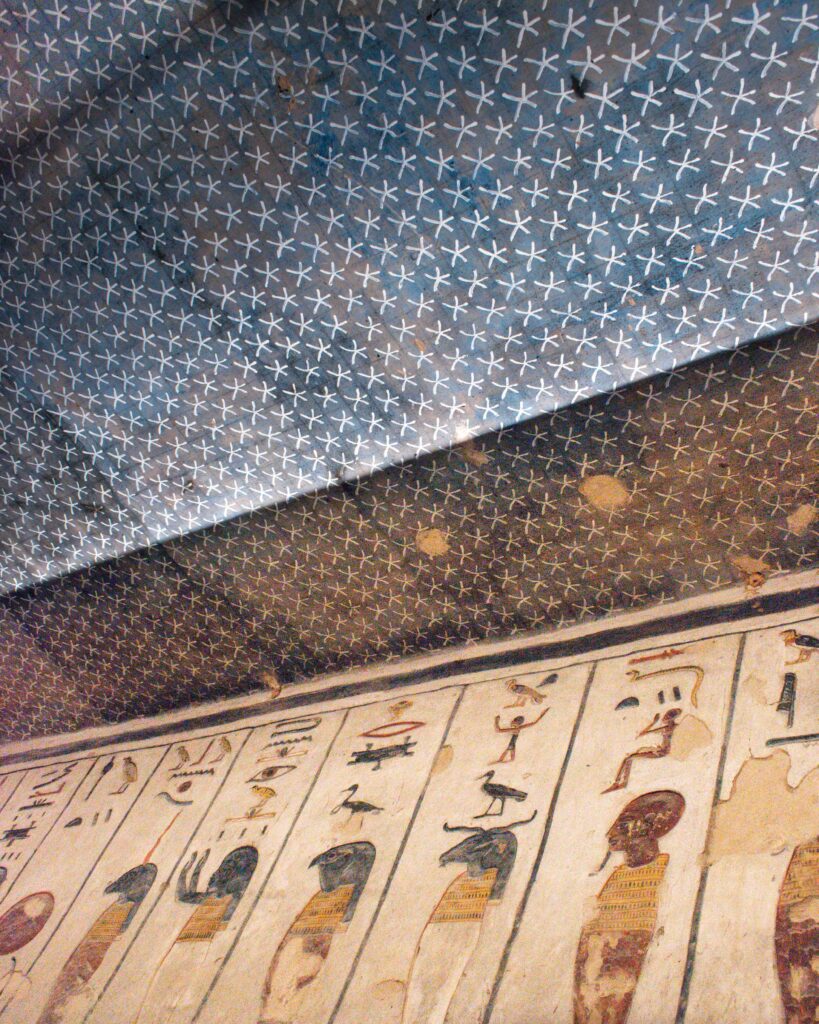

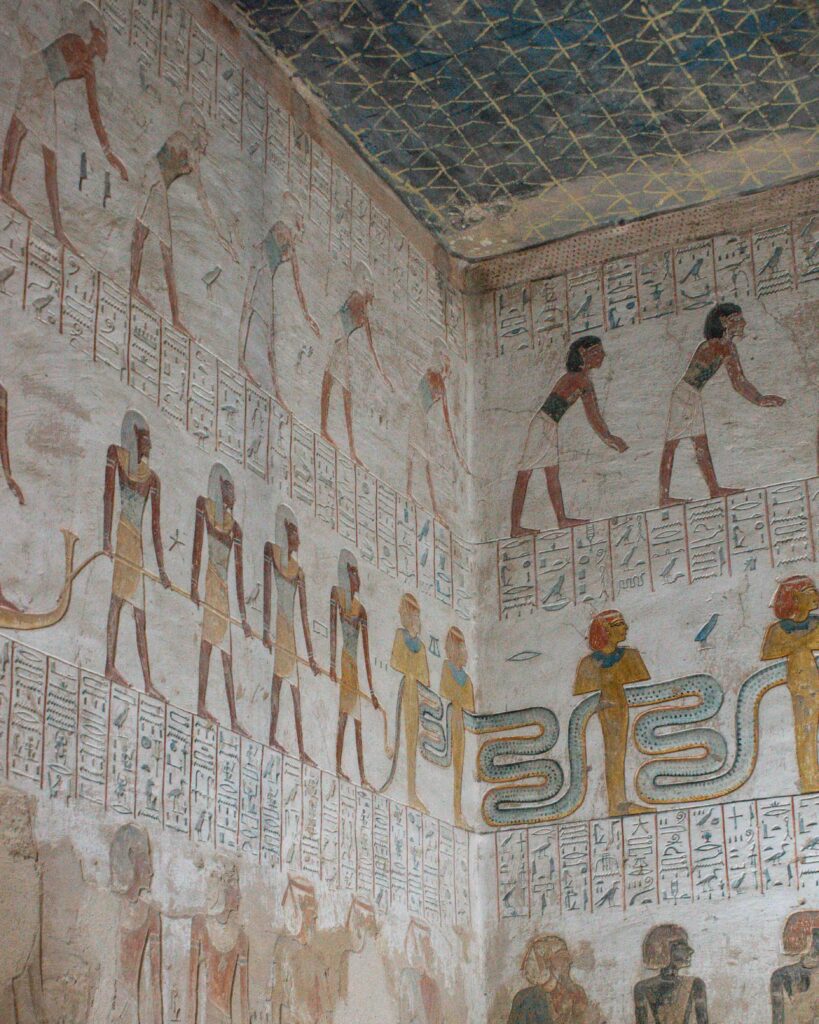

This was the first tomb we went into, and the colours and details blew us away. It is simply beautiful (spoiler alert… little did we know what was to come in the Valley of the Queens!). The decoration is amazingly well preserved, and the walls are covered in extracts from the Book of Gates, the Book of Caverns and the Book of the Heavens. The ceiling of the burial chamber features a magnificent figure of Nut and scenes from the Book of the Day and Book of the Night.

RAMESSES III (KV11)

The second pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty, Ramesses III ruled between 1186 and 1155 BCE. Ramesses III is widely considered to be the last great pharaoh of Egypt. But his reign was a turbulent one, seeing the Trojan wall and the fall of Mycenae causing a surge of displaced people across the Mediterranean. In the eighth year of his reign, a group of “Sea Peoples” attempted to force settlement in Egypt. These groupings were from regions along the Mediterranean who left their homes because of wars and famines. Ramses III’s army eventually defeated them for which he is remembered as the last warrior king.

The discovery of papyrus trial transcripts revealed that Ramesses III was assassinated in a conspiracy instigated by Tiye, one of his three known wives, over which son would inherit the throne.

After Ramesses V and VI, his tomb is one of the best in the Valley of the Kings. On the ceiling, the stars of the Book of the Day and the Book of the Night are beautiful and still amazingly vivid.

RAMSESSES IX (KV6)

Reigning between 1126 and 08 BCE, Ramesses IX was the eight pharaoh of the 12th Dynasty. His reign is best known for the tomb robbery trials, which are recorded in the Abbott Papyrus. When it became clear that royal and noble tombs had been robbed, the Mayor of Karnak accused one of his subordinates, Paweraa, of being responsible. Despite a seemingly extensive trial, no one was officially charged with the crimes.

MERENEBETAH (KV8)

Ramesses II lived for such a long time, that 12 of his sons died before him. It was therefore his 13th son, Merenebetah, that succeeded the throne. This is the second largest tomb in the valley, and as it has been open since antiquity, features Greek and Coptic graffiti. He was the fourth pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty. Merenbetah ruled for almost ten years, from 1213 BCE until his death in 1203 BCE. He is best known for successfully defending Egypt against a serious invasion from Libya.

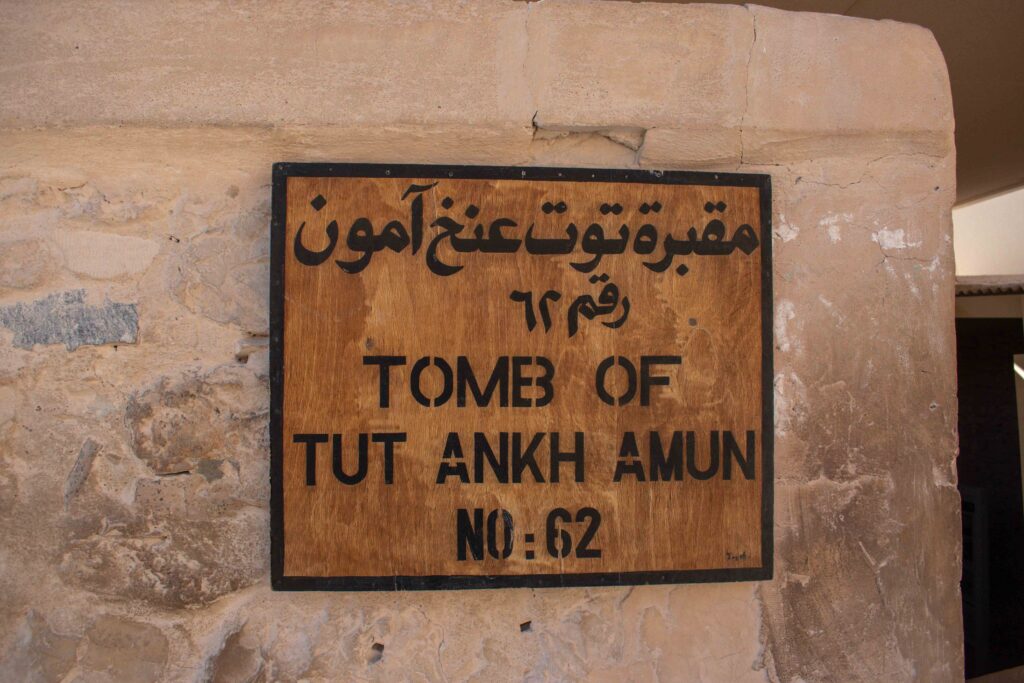

TUTANKHAMUN (KV62)

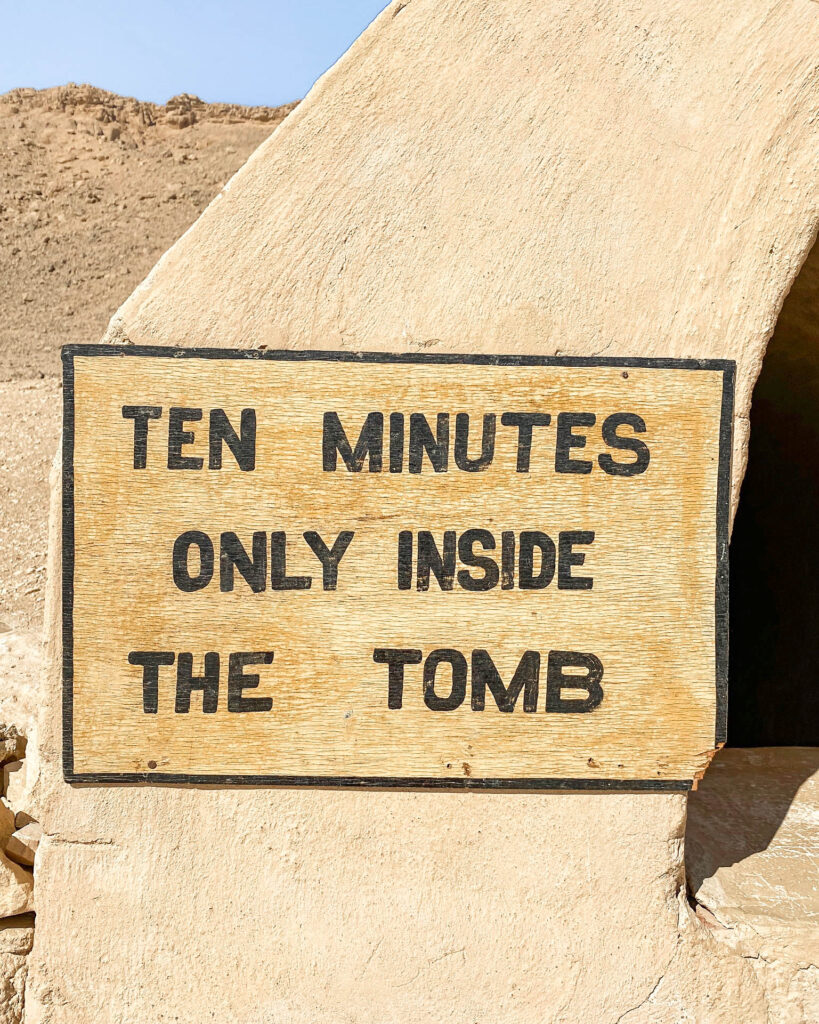

Although we decided not to go into the tomb of Tutankhamun I realise I can’t leave it out! Our guide advised that the tomb was very small, and poorly preserved, and as a separate ticket was needed to enter, we were better off waiting to see the king’s treasures at the museum in Cairo.

Although a minor figure in Egyptian history, the discovery of his intact tomb has ensured that Tutankhamun is probably the most famous of all Egyptian pharaohs. He was the son of Amenhotep IV, who took a revolutionary – and very controversial – decision to swap from worshiping the multitude of gods the Egyptians had previously followed, to follow the cult of the sun god Aten. He changed his name to Akhenaten – beloved of Aten – in the process. Needless to say, this was not a popular move with the high priests and after Akhenaten died subsequent rulers and priests tried to erase as much of this part of history as possible. It is thought that there were two brief periods of rule by pharaohs known as Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten (who may have been Nefertiti). Although interpretations vary, it is thought that priests and advisors then sought to get back to the old ways by putting Akhenaten’s young son Tutankhaten on the throne. He was renamed Tutankhamun (the living image of Amun), to reflect a return to the old ways. At only 8 years old, Tutankhamun found himself ruler of Egypt, married to his half sister Ankhesenamun. They had two daughters, neither of which survived infancy and both of whom were buried in KV 62.

It is thought they ruled Egypt for about 10 years, until Tutankamun’s death at the age of 19. Reasons for his death are disputed, but most likely to be the result of a combination of multiple health disorders (due to years of royal incest), a leg fracture, and malaria. His death brought an end to the 18th Dynasty.

His tomb was famously discovered in 1922 by a dig overseen by British archaeologist Howard Carter, and set off an Egyptomania that has never quite died down! It is thought the tomb was likely protected as the entrance became buried under debris from the construction on KV 9 during the reign of Rameses IV.

TREASURE HUNTING

As we walked around the Valley of the Kings, I asked our guide the question that I suspect they are asked most frequently by tourists… “do you think there any tombs with treasures like Tutankhamun’s yet to be found?” I very much liked his answer. He explained that Egyptology is the “science of maybe”. Whilst modern scholars have a remarkable understanding of Ancient Egypt, new discoveries are made almost daily and just perhaps, there are still more treasures out there to be found. Most tantalisingly, the tombs of Nefertiti, Cleopatra and Ramses VIII are yet to be located. So if you dream of being the next Howard Carter, just maybe there is still a chance for you!

If you want to see more about one of the most amazing discoveries in recent years, check out the Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb on Netflix. It was this series that finally prompted us to realise our long held dream of visiting Egypt.

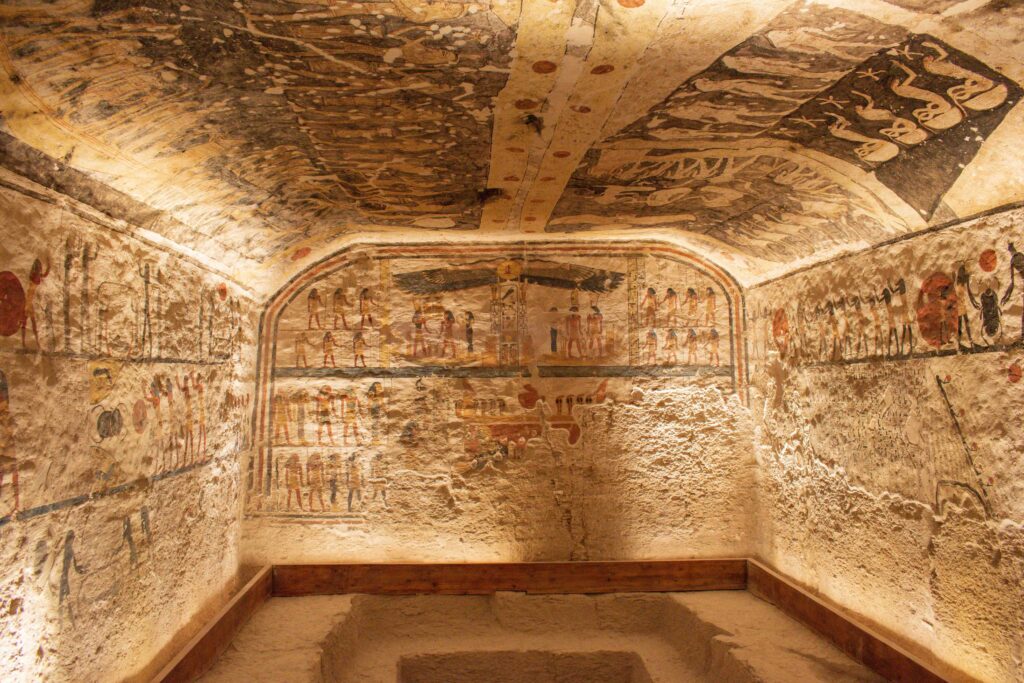

THE VALLEY OF THE QUEENS

The Valley of the Queens is less visited than the more famous Valley of the Kings, so often quieter. On the day we visited, we only saw two other visitors (albeit COVID was still having an impact on global tourism). It was the burial place of the wives of the pharaohs and many of their children. More than 75 tombs have been discovered, mostly dating from the 18-20th Dynasties. Four are open to visit: Nefertari, Titi, Khaemwaset and Amunherkhepshef.

If you decide not to visit the tomb of Nefertari, I’d consider giving the Valley of the Queens a miss. The other tombs are less remarkable than those in the Valley of the Kings, being less elaborate and less well preserved.

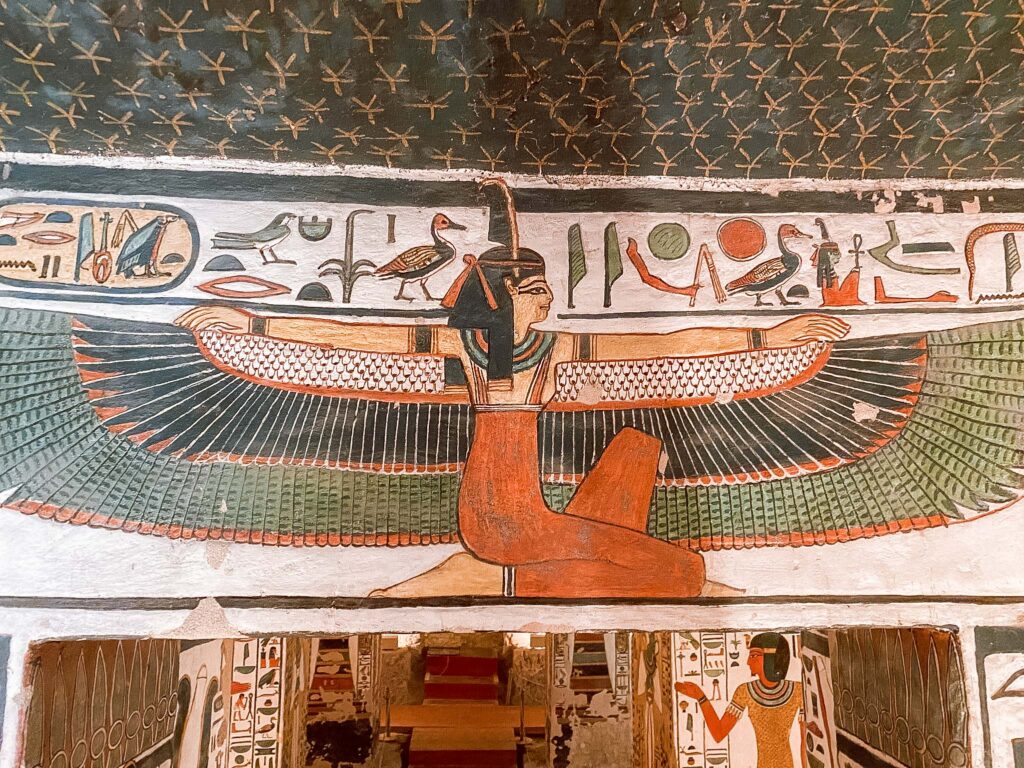

THE TOMB OF NEFERTARI (QV66)

Undoubtedly the most spectacular sight you will see on this list! A visit comes with a hefty price tag (£1400 EGP) but given how astonishing it is, I think it more than worth it.

Nefertari was the first, and favourite, wife of Ramesses II. Her name means ‘most beautiful, beloved of the goddess Mut’. I found Nefertari fascinating, due to the unprecedented role she played in the famous peace treaty between Ramesses II and Hattušili III. After years of aggression, hostilities came to a head with the battle between the Hittite Empire under Muwatalli II and Egypt under Ramesses II at Kadesh in 1274 BCE. After many years of diplomatic exchange, in 1259 BCE a treaty was signed, agreeing to a mutually beneficial alliance between Ramesses II, and Hattušili III (successor to Muwatalli II), leading to over sixty years of peace in the ancient Near East. It was one of the first recorded peace treaties in history. Remarkably, Nefertari and Puduáhepa, wife of Hattušili III, were integral in making it happen. An impressively educated woman, Nefertari exchanged many letters with Puduáhepa, in which both women sought to bring their husbands to agreement.

The walls and corridors of her tomb display 520 square meters of the most vivid, and beautiful, artwork. The colours are unlike anything else we saw in Egypt. Much of the imagery throughout the tomb is derived from Chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead, which lists the things the deceased must know to ensure resurrection.

TITI (QV52)

It is not known which Ramesses Titi was married to – but in her tomb she is referred to as a royal wife, mother and daughter.

KHAEMWASET (QV44)

A son of Ramses III who died young, although little is known about his age or cause of death.

AMUNHERKHEPSHEF (QV55)

A son of Ramses III, who died in his teens. The colours are well preserved, but shielded behind Perspex sheets, so harder to observe fully, compared to the tombs of the Valley of the Kings.

THE PRACTICAL STUFF

Check out my guide to the temples of Upper (southern) Egypt for more practical information, including advice on tipping, how to avoid scams and amenities at each sight.

Guides in the Tombs – it is worth noting that tour guides are no longer allowed to enter the tombs in either the Valley of the Kings or Queens. This is to help prevent congestion. You will be given information regarding the site outside the tomb, and then head inside to explore on your own. You may therefore want to bring information with you to refer to once inside the tomb as there is simply so much to see. The Valley of the Kings and the Theban Tombs by Alberto Siliotti is a great pocket guide for detailed information on the tombs (of course, you can also refer to the relevant sections of the excellent guide you’re currently reading!).

Costs – we visited all of these sites as part of our itinerary aboard the SS Sudan, and as this included a private guide and all transport, I think it offered us fantastic value. You can read more about my thoughts on whether a Nile cruise offers value for money here. Costs for individual entry are below (excluding photography tickets and extras):

- Luxor Temple – £160 EGP (£4/$5)

- Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple – £140 EGP (£3.50/$4.50)

- Philae Temple – £100 EGP (£2.50/$3.20)

- Edfu – £60 EGP (£1.50/$2)

- Kom Ombu – £80 EGP (£2/$2.50)

- Karnak Complex – £160 EGP (£4/$5)

- Valley of the Kings – £240 EGP (£6/$8)

- Valley of the Queens – £50 EGP (£1.30/$1.60)

- Tomb of Tutankhamen – £300 EGP (£7.60/$10)

- Tomb of Seti I – £60 (£1.50/$2)

- Tomb of Nefertari – £1400 EGP (£35.50/$45)

Whilst these ticket prices on their own are amazingly reasonable to see some of the world’s greatest treasures, if you are visiting all of the temples and tombs, costs add up quite quickly. So if you plan on spending several days around Luxor and visiting several of the sites, I recommend buying a LUXOR PASS. The premium pass (US$100) includes the tombs of Seti I and Nefertari. The pass can be bought from the Department of Foreign Cultural Relations at the Ministry of Antiquities in Zamalek (Cairo) or from the Public Relations Office in the Luxor Inspectorate, behind the Luxor Museum on the east bank of Luxor. The office is open 9am to 3pm each day, Monday to Friday. You need to provide a photocopy of your passport and a passport photo.

Don’t forget to have a look at my other guides to Egypt for inspiration in planning you trip – in particular, be sure to check out my reference guide to the temples of southern Egypt if you want to find out more about the sights of Upper Egypt.

Leave a Reply