I can’t possibly hope to provide a comprehensive guide to all of the temples and tombs of the southern Nile – nor am I remotely qualified to do so (as much as I came back from Egypt dreaming of becoming an Egyptologist!). Instead, I hope this guide offers the introduction that I wish I had before we went to each temple or tomb. There is simply so much to see and take in, and guides only have the chance to give a limited amount of information on each site, that it can be difficult to put it all into context. Our guides were incredibly knowledgeable, and took us to see all the highlights at each location. But given Pharaonic history spans a period of over 3,000 years, I wished I had something to refer to in order to put each site into the wider context of the various dynasties and time periods.

Fair warning, this is therefore going to be a very (very!) long one. Given the sheer volume of information, I have separated out my reference guide to the Valley of the Kings and Queens.

So, settle in with a cup of mint tea and sit back for an Egyptian history lesson… and hopefully enough to convince you that Egypt absolutely must be on your bucket list.

ANCIENT EGYPT IN A NUTSHELL

“Ancient Egypt” is generally taken to refer to the period from the unification of Egypt under its first king, Narmer, around 3,100 BCE, until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE. This 3,000 year span is usually divided into three kingdoms: the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom. The stretches in between these kingdoms are known as the intermediate period, and the whole epoch is generally divided into 30 dynasties.

Although power was concentrated along the Egyptian Nile, at various times, Egyptian control extended into modern day Sudan, Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria, Israel and Palestine. Egypt was also occupied by other powers, with the Persians, Nubians, Greeks and Romans all conquering Egypt at different points.

Magnificent remnants of the great Pharaonic civilisation of ancient Egypt can be found right along the length of the River Nile, but broadly they can be divided into those of Lower Egypt and those of Upper Egypt. Most temples in Lower Egypt (rather confusingly, the northern part of the country) date to the time of the Old Kingdom (2649-2134 BCE) before Egypt’s kings were known as Pharaohs. This includes the famous pyramids and Sphinx at Giza. The structures of the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE), associated with some of the most famous Pharaohs like Ramses the Great and Tutankhamun, are concentrated in the south, in Upper Egypt. This guide will focus on the southern monuments and tombs.

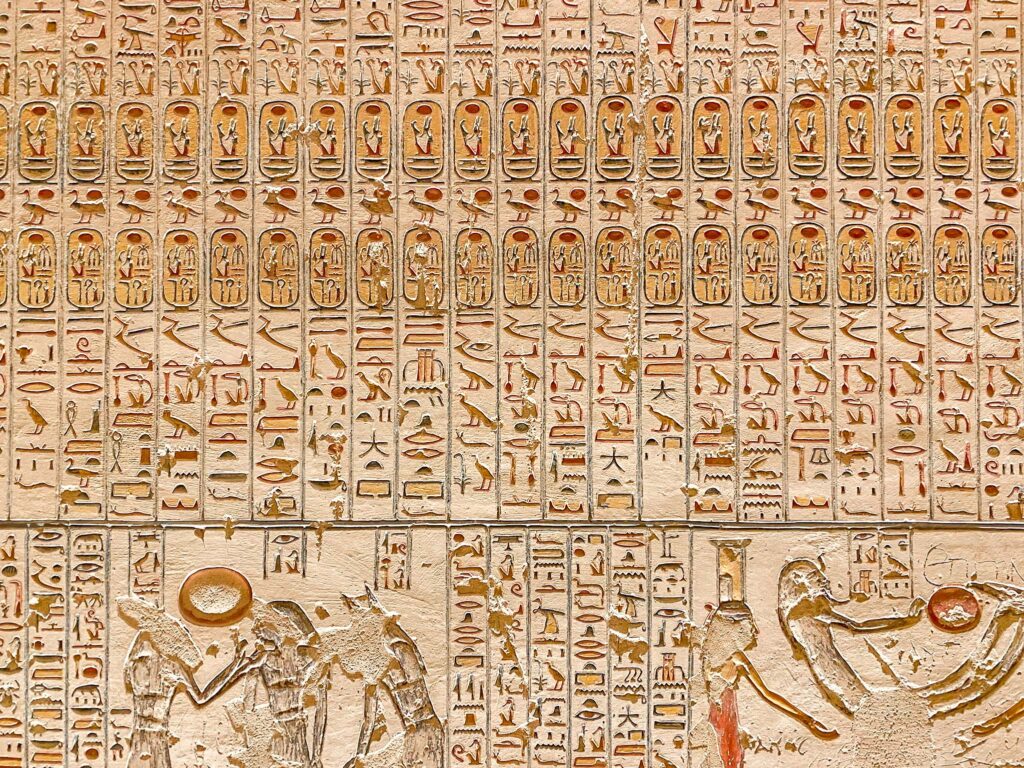

THE SYMBOLS AND HIEROLGYPHS

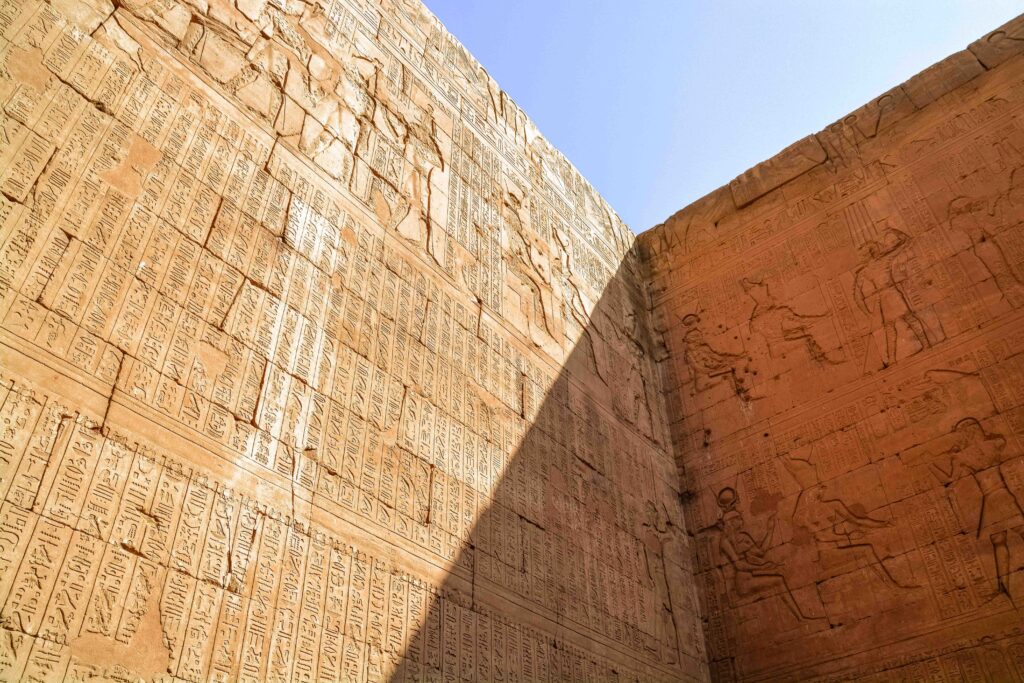

The writing of the ancient Egyptians – the hieroglyphs – are more akin to art work than our modern alphabet. The carved stone walls of temples and the amazingly preserved papyrus are beautiful.

Hieroglyphs were unintelligible to modern scholars until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799. This famous slab depicted text in three languages – including hieroglyphics – and critically, a paragraph in Ancient Greek which could be read. In an entirely predictable turn of events, a race began between the British and French to be the first to decode the Egyptian symbols. An English physicist, Thomas Young, was one of the first to make headway. But those dastardly French eventually won, with the famous Egyptologist, Jean-François Champollion, finally making the breakthrough in 1822 that allowed us to finally read hieroglyphs. The British Museum (where the Rosetta Stone now resides) has some wonderful copies of Young and Champollion’s handwritten deciphering online.

Our guides taught us to recognise a few of the most important, and nothing beat the child like excitement we felt whenever we spotted a symbol we knew amongst the mass of intricately carved reliefs… never mind that we couldn’t read a single other thing on the wall! So here are a few of the most common so that you can have your own moment of feeling like a great explorer!

THE SIGHTS

The vast majority of cruise itineraries follow the route between Luxor and Aswan, usually offering a choice of four or seven day itineraries. The sights below are set out in geographic order, from south to north.

THE NUBIAN MUSEUM, ASWAN

The history of southern Egypt is inextricably linked with the Nubian civilisation. An independent kingdom, which flourished between 3300 to 1300 BCE, Nubia extended from the Nile River valley, near the first cataract in Aswan, all the way east to the Red Sea and south to Khartoum in modern day Sudan.

The museum displays a section of the 3,000 artefacts it owns, in a well laid out series of dimly lit halls. For me, the highlights were:

- A mummified ram with a golden fleece from the Temple of Khnum on Elephantine Island, dating from the Ptolemaic (Greek) period. Khnum was the ancient Egyptian god of fertility, associated with water and with procreation;

- Statue of Ramses II. Almost every museum in Egypt has a statue of Ramses the Great, and the Nubian Museum is no different with this eight-metre tall offering;

- Carved bust of the Nubian King, Tahraqa. Under King Taharqa, Nubia’s empire reached its greatest extent, stretching from present-day Khartoum to the Middle East;

- Model of a Nubian army formation. Reliefs tell us that since the Middle Kingdom, ethnic Nubians fought as part of the Egyptian army. The museum has a replica of wooden models representing such a formation from the 11th Dynasty. The original is in the Cairo Museum.

The Museum also houses a fascinating series of photographs documenting the efforts to rescue, and move, the temples left underwater by the creation of the High Dam in 1961. Remarkably this salvage and restoration project involved moving, brick by brick, the vast temples of Philae and Abu Simbel.

Aswan was probably our favourite city in Egypt. The setting on the banks of the Nile at the First Cataract, marks the historic southern border of Egypt and is simply very picturesque. It has a slower pace than other Egyptian cities, and the influences of the African continent to the south are evident, not least in the brightly coloured Nubian houses.

Other popular sights in Aswan include the Nubian Village, Elephantine Island and the Unfinished Obelisk. The Tombs of the Nobles, dating from the Old and Middle Kingdoms, are cut into the cliffs opposite Aswan. The city is the jumping off point for Lake Nasser and the mighty temple of Abu Simbel to the south.

A number of visitors come to Aswan purely to stay at the famous, and very historic, Old Cataract Hotel. Agatha Christie is said to have written part of Death on the Nile here, and former guests read like a who’s who of the early 20thC most famous Europeans. I wholeheartedly recommend splashing out on a stay here – full review coming soon!

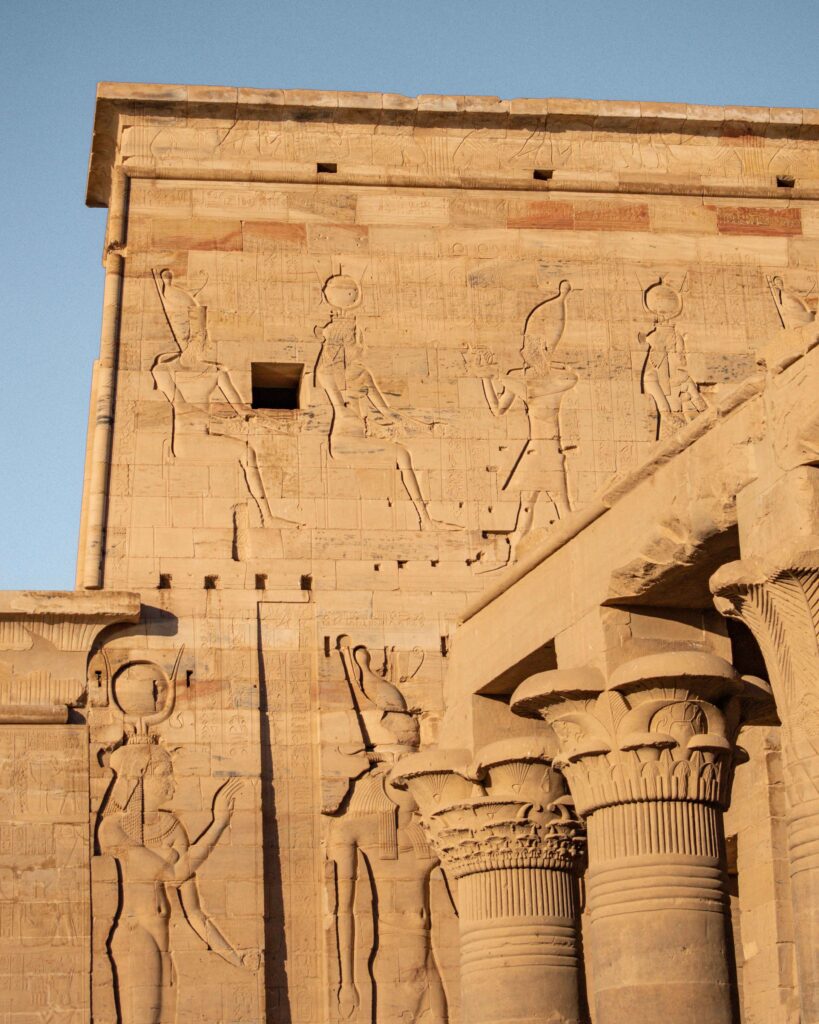

TEMPLE OF ISIS AT PHILAE

Dedicated to the goddess Isis, this temple was one of the very last to be built in the classical Egyptian style. The oldest parts were built by Nectanebo I, the last native king of Egypt around 380 BCE. However, much of the temple currently standing was built by Ptolemy II and added to for the subsequent 500 years until the reign of Diocletian in AD 305. This makes it almost new in comparison to many of Egypt’s other truly ancient sites!

Isis was one of the most important deities in the ancient world. She was the wife of Osiris and mother of Horus. She was associated with funeral rites and made the first mummy from the dismembered parts of Osiris, after he had been killed by his brother Seth. After resurrecting Osiris and giving birth to Horus, she was also the giver of life, a healer and protector of kings.

She was represented with a throne on her head and was sometimes shown breastfeeding the infant Horus. In this position she was known as “Mother of God.” Philae is her most famous temple, but such was the spread of her cult that there was even a temple dedicated to her as far afield as London.

THE TEMPLE FEATURES

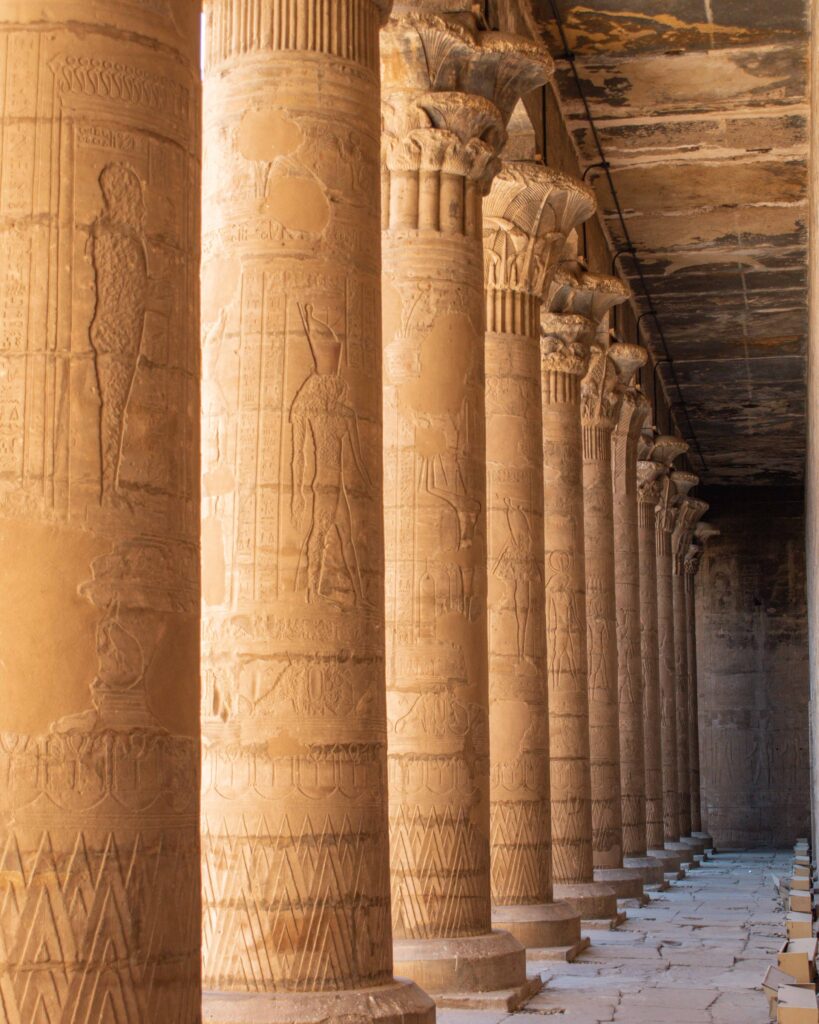

When you first enter the complex, two rows of colonnades lead to the first monumental gate – known as a pylon in Egyptian architecture – of the temple. The tops of the columns give the first clue that the temple dates from the Ptolemaic era. Earlier Egyptian temples have plainer columns decorated with the lotus (the symbol of Upper Egypt) or a papyrus (the symbol of Lower Egypt). The Greeks and Romans introduced more intricate flower designs.

The main gate has many of the features you will see in other temples around Egypt. The two 60ft towers have holes cut into the top, through which large flags would have been hung during festivals. On the walls of the gate, you will see a motif common on Egyptian temples. Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysus (117 – 57 BCE) is depicted holding the enemies of Egypt by the hair and holding a mace above his head. This ‘vanquishing of enemies’ is a common feature throughout the temples we saw as the Pharaohs sought to portray themselves are heroic and powerful leaders.

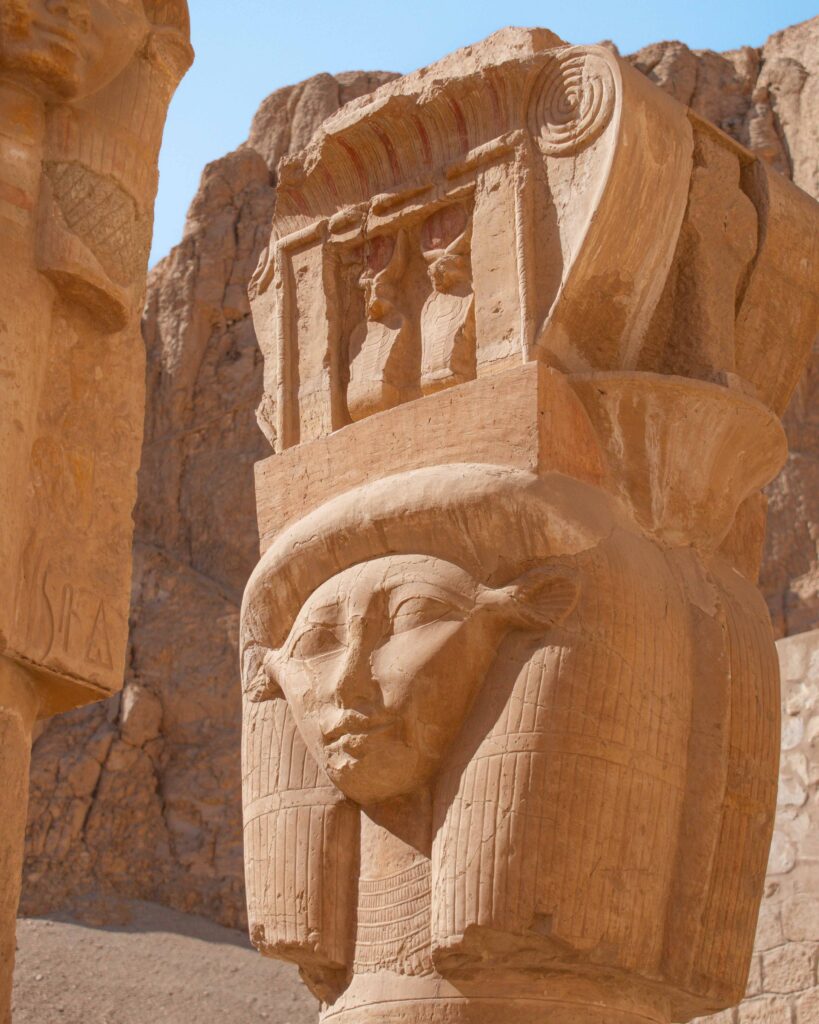

To the left of the central court, you will find the mammisi, or birth house. This was a common feature of Ptolemaic temples, and again marks them out from earlier temples which did not have such a feature. These small temples were dedicated to scenes of the birth and upbringing of a divine child – in this case, Horus. The birth house is covered on three sides by one of my favourite features of the temple – a row of Hathor headed columns. Hathor was the goddess of women and fertility. The face slowly breaks into a smile as you progress along the columns.

COPTIC HISTORY

Most of the faces, legs and arms on the temple reliefs have been chiselled away. We saw this time and time again in Egypt. During the ‘Coptic period’ of Egyptian history (usually defined as AD 3rd-7thC), when Christianity become the dominant religion, many of the earlier temples were converted to places of Christian worship. Any examples of bare skin were covered over with chisel marks to make the reliefs more appropriate for the new audience. Such chiselling was not the exclusive preserve of the Christians. Earlier Pharaohs likewise covered over cartouches and motifs of their predecessors they wished to side line – such as at Karnak and the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut (more below). Other evidence of this later layer of Egyptian history can be seen in the distinctive Coptic crosses carved into serval of the walls of the Temple at Philae.

KIOSK OF TRAJAN

This unfinished monument is attributed to Trajan, the Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, who is depicted as a Pharaoh on the reliefs. However, much of the structure dates to an earlier period, possibly from the reign of Augustus (27 BCE – AD 14). The kiosk was a great favourite of Victorian artists, and would have been one of the most recognisable images of ancient Egyptian temples for the European public.

AGILIKA ISLAND & MOVING PHILAE

The setting of Philae Temple must be one of the most romantic in Egypt. As it sits on an island, you need to catch a small motorboat or felucca to access the site. However, this is not the original site of the temple. It is actually located on Agilika Island – though most people will still just refer to it as Philae. When standing on Agilika Island you can see the remnants of poles sticking up above the water a short distance away, which mark the original site of the temple.

In 1902 the British finished construction on a new dam at Aswan, designed to regulate the annual floodwaters to support more predictable harvests. However, the dam also had the effect flooding Egypt’s ancient sites south of the dam for much of the year. If you had visited Philae between 1902 and 1960, you would likely have been exploring the temple by boat, floating among the ruins and peering into the water at the temple below. Although the structure was shored up to preserve it, unfortunately the spectacular colours of the reliefs were washed away. Between 1972 and 1980, UNESCO led a remarkable project to move the entire temple, in about 40,000 pieces to nearby higher ground. You can find some incredible footage here of the salvage operation and the tags numbering the blocks are still visible in some places.

KOM OMBO

Commissioned by Ptolemy VI, most of the temple of Kom Ombo was actually completed by Cleopatra’s father, Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos. Construction took place between 180-47 BCE, although there is evidence that it stands on the site of a much earlier temple.

The ancient Egyptians believed that temples were the homes of the gods and goddesses. Every temple was therefore dedicated to a god or goddess who was worshipped there by the temple priests and the Pharaoh.

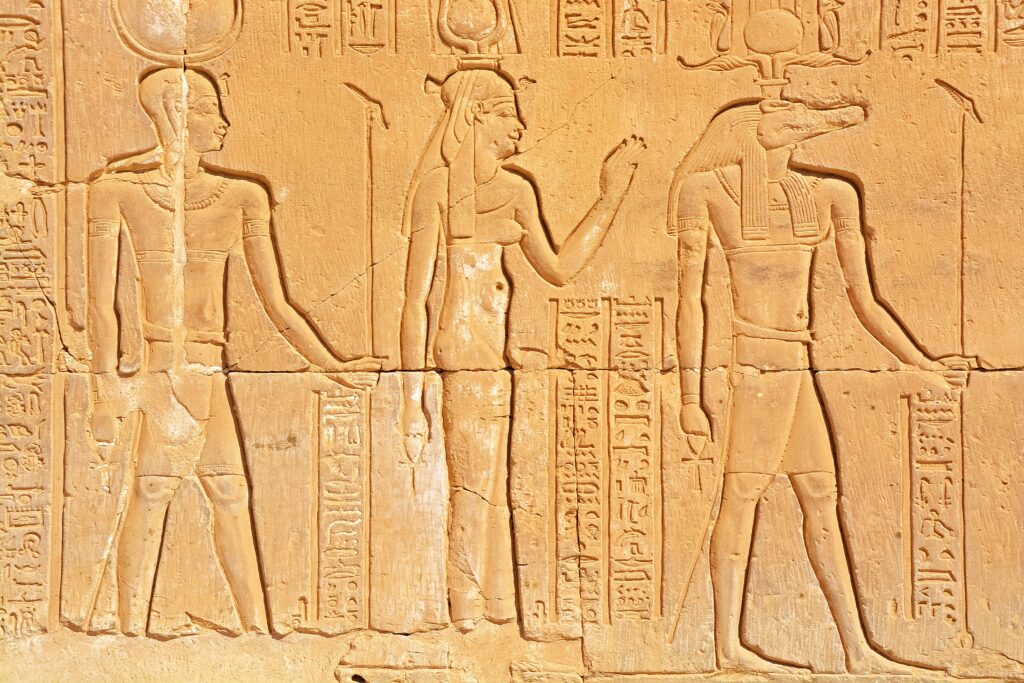

Kom Ombo is unusual as it is dual-dedicated, meaning it is devoted to two different gods. The left (western side) of the temple was dedicated to the falcon headed Haroeris (Horus the Elder), and the right (eastern side) to the crocodile god Sobek. The two sides of the temple are symmetrical and house two courts, two colonnades, two hypostyle halls, and two sanctuaries. Originally, both sides of the temple would have had their own gateway and chapel.

Sobek was thought to be the god who created the River Nile, and was also associated with fertility and rebirth. The cult of Sobek was one of the earliest in Egypt. He first appeared on a relief from the reign of King Narmer, the first king of the first dynasty. The worship of Sobek continued into the Ptolemaic and Roman period, principally at Kom Ombo.

Haroeris is a manifestation of the famous Egyptian deity Horus. He was one of the most important gods in Egyptian mythology. The son of Osiris and Isis, he is depicted a man with the head of a hawk or fully as a falcon. He was the god of the sky, and the divine protector of the Pharaohs. He was worshipped throughout Egypt, and especially associated with the temple at Edfu (more below). Many of the stories about Horus concern his battles against, and eventual victory over, his uncle Seth, who murdered Horus’ father Osiris. Although there are different interpretations, given its proximity to the main Horus temple at Edfu, it is thought he was known as Haroeris at Kom Ombo to avoid confusing worshippers as to why there were two temples for the same god.

The temple is most famous for two masterpieces. The first is a detailed Egyptian calendar, detailing the Nile flood and harvest seasons, and the days of each month.

The second is at the back of the temple, within an area that was used as a hospital. A relief depicts early surgical tools, including scalpels, syringes, scissors and forceps. On the left side of the relief two goddesses sit on birthing chairs.

Kom Ombo is also known as having one of the best surviving nilometers. Nilometers measured the water level of the Nile River during the annual flood. This was then used to predict the outcome of the annual harvest, the taxes to be imposed, as well as the prices of foodstuffs. This fantastically bureaucratic system was unsurprisingly introduced by the Greeks and Romans.

THE CROCODILES

Overhunting and the creation of the High Dam have led to the extinction of crocodiles from the Nile north of the dam, but the area around Kom Ombu was once teaming with reptiles. At this temple dedicated to the crocodile headed god Sobek, priests would therefore raise sacred captive crocodiles inside the temple. Over 300 crocodile mummies have been found at the temple site, many of which are now on display at the nearby Crocodile Museum. This little museum is well worth a visit. It is well laid out, and has plenty of information in English. I also appreciated that whoever laid out the museum clearly had a sense of humour – as you walk into the museum you come eye to eye with a fairly terrifying, 4m long, mummified crocodile!

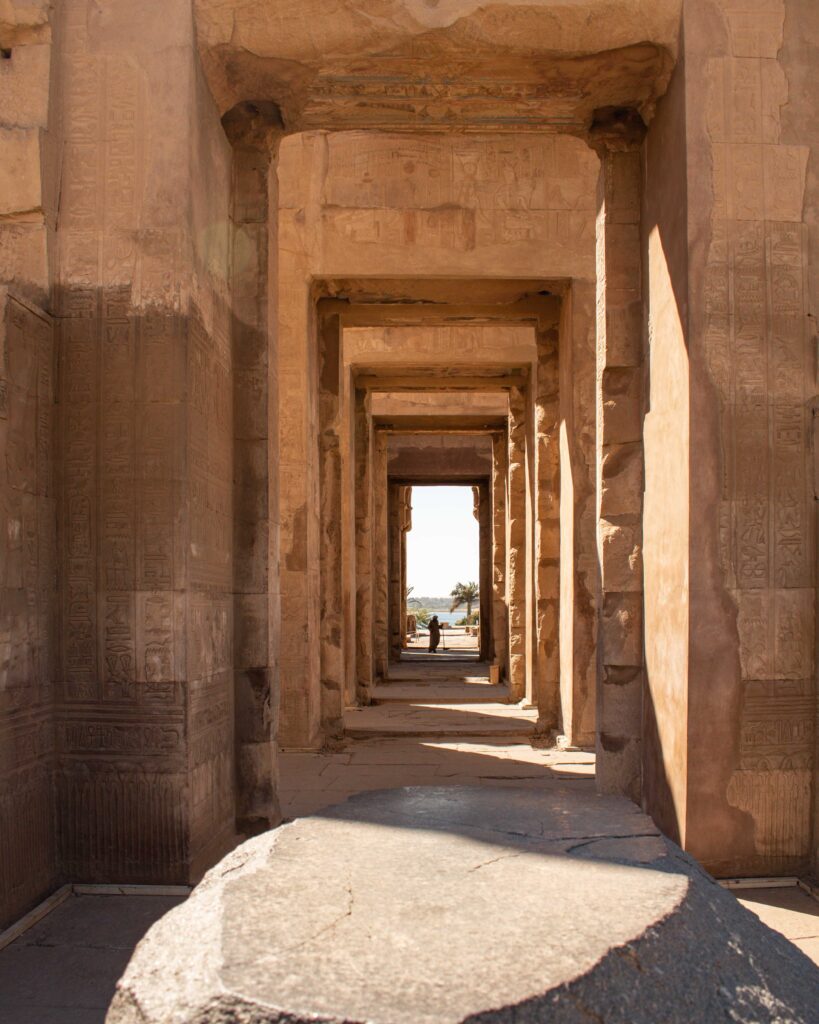

EDFU TEMPLE

This magnificent Ptolemaic temple, built between 237 and 57 BCE, is one of the best preserved in Egypt. With front pylons reaching 118 ft and its width spanning 450ft, this is also the tallest of the surviving Egyptian temples. This was one of my favourite sites in our whole Egyptian adventure – during our visit, the 15 guests aboard our Nile cruise were the only people at the temple, and it was bathed in a glorious late afternoon glow.

The walls of the temple also bear witness to some of the turmoil of this period of Egyptian history. All but a few of the cartouche are empty. The priests, not entirely sure who the current Pharoah was given ongoing fighting, decided it was safer to include no name, rather than get it wrong and risk the wrath of whoever did hold power at that moment!

HORUS AND SETH

The temple at Edfu is dedicated to the falcon headed god, Horus, and sits on the spot the ancient Egyptians believed to be the exact location of the mythological battle between the god Horus and his evil uncle Seth. Originally known as Wetjeset-Hrw, or ‘The Place Where Horus is Extolled’, the modern Arabic name, Edfu, came from the Coptic name, Etbo.

The tale of Horus and Seth is one of the great mythologies of ancient Egypt. It starts with Osiris (the firstborn son of Geb, god of the earth, and Nut, the goddess of the sky) ruled Egypt with his sister-wife, Isis. Their reign was prosperous and peaceful, but Osiris’ brother, Seth, decides to kill Osiris so he can be king, by chopping him into many pieces and scattering the remains across the Earth.

Grief stricken, Osiris set out to gather all of the pieces of her husband, to bring him back to life. She manages to reassemble him at Abydos, but his penis is missing. She sculpted one out of mud, and using her magical powers, is able to conceive a son with him. Horus.

Once Horus came of age, he asked the assembly of gods under the supreme authority of Ra (the sun god), to take his legitimate place and assume the throne of his father and usurp his uncle Seth. Many battles were to follow between uncle and nephew – including many where Seth turned himself into a hippo – before Horus eventually defeated Seth. The ancient Egyptians saw their battle an eternal struggle between good and evil. From this point on, every King of Egypt identified with Horus while they ruled and subsequently with Osiris after they had died.

This epic story is set out on the walls of the Temple of Edfu in giant reliefs known as the Passage of Victory – be sure to look out for all the hippos!

On the wall opposite the Passage of Victory, is a small relief setting out the Egyptian counting systems. The numbers 1 – 100,000,000 are shown.

FEAST OF THE DIVINE UNION

For the ancient Egyptians, temples were not only places of worship, but the earthly homes of the gods. Festivals therefore often revolved around the occasions on which the gods were thought to travel from their respective temples to meet each other.

Hathor was the daughter of Ra and the goddess of women, beauty, love and fertility. She is depicted in three forms; as a cow, as a woman with the ears of a cow, and as a woman wearing the headdress of a cow’s horns. She is the wife of Horus. Each year the goddess travelled 180km from her temple at Dendera to visit Horus at Edfu temple to celebrate the Feast of the Divine Union. This journey is depicted on the inside of the main gate of Edfu temple. Both are depicted in ceremonial barges, making the journey to see each other.

INCENSE ROOM

My favourite feature at Edfu was a small room – known as the laboratory – on the western side of the temple which was dedicated to the creation of incense.

The burning of incense was central to the worship of the gods for ancient Egyptians, and large quantities were burned every day. Although some of the ingredients were indigenous to Egypt, many had to be imported as exotic fragrances like myrrh, frankincense, cinnamon, cassia, and Galbanum were preferred. Such a trade mission is recorded in detail on the walls of the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut (more below).

The walls of the laboratory at Edfu are covered in recipes for specific incense blends. Most excitingly for historians, this includes a formula for kyphi. This blend of honey, wine, dried fruit, precious resins, and spices such as frankincense, myrrh and cinnamon, was the most popular temple incense. Even the proportions of each ingredient are recorded precisely.

The itinerary for the Steam Ship Sudan includes a visit to an incense workshop in Luxor, during which a local guide took us through the creation of all the most popular scents – and gave us the chance to test out many. We came away with a small bottle the most intense mint oil I have ever smelled. A few drops in hot water will steam away any cold I ever get in the future!

THE EAST AND WEST BANKS OF LUXOR

Luxor is the modern-day Egyptian city that sits atop an ancient settlement that the Greeks named ‘Thebes’ and the ancient Egyptians called ‘Waset.’ The River Nile divides Luxor, with the West Bank and the East Bank holding different roles in ancient Egyptian beliefs and society. The West Bank was thought to symbolise Death, and the East Bank, Life. Therefore all of the tombs and mortuary temples in Egypt are found on the western side of the Nile, and all of the temples (as the homes of the gods) are found on the east. There are simply so many sites and museums here, that you could easily fill three or four days and not run out of fascinating places to visit. Not without reason, it is known as “the world’s greatest open air museum”. Be sure to also check out my reference guide to the Valley of the Kings and Queens.

We had read and dreamed so much about Thebes, and it had always seemed so far away, that but for this delicate allusion to the promised sheep, we could hardly have believed we were really drawing nigh unto those famous shores. About ten, however, the mist was lifted away like a curtain, and we saw to the left a rich plain studded with palm-groves; to the right a broad margin of cultivated lands bounded by a bold range of limestone mountains; and on the farthest horizon another range, all grey and shadowy.

Amelia Edwards – One Thousand Miles Up the Nile (1877)

There are multiple accommodation options in Luxor, with something to suit all budgets and styles of travel. For a slice of history, check out the famous Sofitel Winter Palace (full review coming soon) or for something serene and more under the radar, the beautiful El-Moudira Hotel on the West Bank can’t be beaten. Just be aware that the location of El Moudira is more remote – and that is part of its charm – and you will need to take taxis or boats to all sites. For something more central on a budget, the Nefertiti Hotel on the east bank and Djorff Palace on the west bank were popular with fellow travellers.

KARNAK TEMPLE

It is a place that has been much written about and often painted; but of which no writing or art can convey… the scale is too vast; the effect too tremendous.

Amelia Edwards – One Thousand Miles Up the Nile (1877)

Given the labyrinthine scale of Karnak, and the excellent resource most guidebooks offer on the temple, I don’t plan to reproduce it all here! But a few brief facts…

Probably the most famous of Luxor’s temples, construction was started by Senusret I during the Middle Kingdom with a temple dedicated to the god Amun (considered the king of the gods at this time). He was depicted in many forms, but was often shown with a ram’s head – accounting for the many ram-headed sphinxes at Karnak. Areas dedicated to Amun’s consort Mut (the mother goddess) and their child, Khonsu (the god of the moon and time) were added later. Together, these three gods formed the Theban triad of deities worshipped in the Luxor area.

Karnak became much more than just a religious site, as the ancient Egyptians came to consider it the contact point between the god Amun (the supreme ruler of the universe) and the pharaoh (the supreme ruler on Earth). This link ensured that successive pharaohs sought to add to the temple, growing it to the massive size (nearly 2 sq km) it is now.

GREAT HYPOSTYLE HALL

After the pyramids, this is the most visited ancient site in Egypt. Built in the 19th Dynasty, it covers a staggering 5,000 m2 (54,000 sq ft). 134 papyrus shaped columns originally supported a roof, over 20 metres high. The sandstone pillars are covered in intricate carvings, reliefs and inscriptions. During COVID, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities took advantage of the closure of the temple complex, and embarked on a project to restore the etchings to their original vibrant colours.

HATSHEPSHUT’S OBELISK

Hatshepsut was an 8th Dynasty wife and half-sister of Thutmose II. When he died, she stepped in to act as regent for her husband’s infant heir, Thutmose II, the son of the Pharaoh by a secondary wife). But instead of crowning herself Queen, she declares herself a Pharoah. During her reign she was always depicted as male in monuments and statues. She ruled Egypt – apparently wildly successfully – for the next 22 years. Thutmose III clearly harboured quite the grudge that Hatshepsut had kept the throne from him for so long, as a staggering 20 years after she died, he set about having all mentions of her erased, defaced and removed throughout Egypt. At Karnak, her name and image were removed, and the base of her towering obelisk bricked up. Find out more about Hatshepsut below, and her mortuary temple.

THE AVENUE OF THE SPHINXES

An avenue of human headed sphinxes of over one and a half miles (3 km) connected the temples of Karnak and Luxor, to be used once a year during the Opet Festival. After seven decades of restoration, the avenue was reopened in a grand parade, re-enacting the Opet Festival, in 2021.

The Opet Festival took place during the second month of the inundation season (the period during which the Nile River floods its banks). The priests would place the statues of Amun, But and Khonso onto ceremonial barges and then carry then down the Avenue of the Sphinxes, to Luxor Temple. The Pharoah would then undergo a series of religious ceremonies in the temple, emerging imbued with the powers the royal ka, or life force, and renewing his divine kingship. Festivities could last anywhere from 11 to 27 days.

LUXOR TEMPLE

Built by the New Kingdom pharaoh Amenhotep III (1390-52 BCE), Luxor temple is also known as the Southern Sanctuary. It’s amin purpose was for use during the annual Opet Festival, when the statues of Amun, Mut and Khonsu were brought from Karnak, along the Avenue of Sphinxes, to be reunited during the second month of the inundation season (called akhet). Once the procession reached Luxor, the statue of Amun and the Pharaoh would enter the temple and undergo a series of ceremonies. When the king emerged, he would have been imbued with the powers of the royal ka (the life force or spirit), giving him the might of Amun-Ra, and renewing his divine kingship.

LAYERS OF HISTORY

One of the things I liked most about Luxor temple, is that the various periods of Egyptian history are all so visible here. Originally built as a temple to the gods of the Ancient Egyptians, it was subsequently converted into a Coptic church. The temple then lost for thousands of years, buried beneath the streets and houses of Luxor. Eventually, using parts of the existing structures sticking up out of the ground, the mosque of Sufi Shaykh Yusuf Abu al-Hajjaj was built on top of the site in the 14th century.

When the temple was excavated in 1885, the mosque was carefully preserved, and now forms an integral part of the site. Looking at the mosque from inside the temple complex, you get an idea for how deeply the temple was buried. The intricately carved doorway, now several metres up in the air, was at ground level when the mosque was built.

THE MORTUARY TEMPLE OF HATSHEPSUT

EGYPT’S GREATEST QUEEN

Although Hollywood has immortalised Cleopatra, and you might just have heard of Nefertari, the ultimate female superstar of Pharaonic history has got to be Hatshepsut (c. 1507–1458 BCE). She was only the second woman to rule Egypt, not just as a Queen, but as a King and a Pharoah. She was the fifth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty.

She was the eldest daughter of King Thutmose and Queen Ahmose. At the age of about 20, she married her half brother Thutmose II, as was tradition to legitimise claim to the throne as the son of a lesser wife. They ruled Egypt jointly for 14 years, before Thutmose II died. On his death, the claim to the throne passed to his eldest son (by one of his minor wives), but he was a child of only 3 years old. Hatshepsut was appointed queen-regent to her stepson, until she officially assumed the role of King of Upper and Lower Egypt in the seventh year of her regency.

On taking the throne, Hatshepsut adopted a new royal name, Maatkare, meaning ‘Truth is the soul of the Sun’. Given how unusual it was for a female to rule, she chose to depict herself as a King, with the traditional false beard on her chin and a more male figure in order to legitimise her position. Her incredible 21 year reign was one of the most prosperous in Egyptian history, marked by a booming economy, trade missions and public works.

Despite this, Hatshepsut was almost erased from history – including being left off the famous Kings List at Abydos, and her monuments defaced or destroyed. Scholars disagree on why this happened. One theory is that when Thutmose III eventually did assume power after Hatshepsut’s death, he sought to take his revenge against her having waited so long for the throne. However, as it is thought that he only set about having her cartouches chiselled off walls and all images of her removed in the final decade of his 32 year reign, others believe it was about erasing the precedent of a strong female leader. Whatever the reason, the result was that historians knew very little about this amazing rule until 1822 when the hieroglyphics on her Mortuary Temple were finally decoded.

THE TEMPLE

Sculpted from limestone, three staggered, almost modern geometric terraces are set into the rocky cliffs behind. Construction took over a decade, and the site chosen due to its long association with the goddess Hathor, responsible for protecting the dead on their journey to the Underworld.

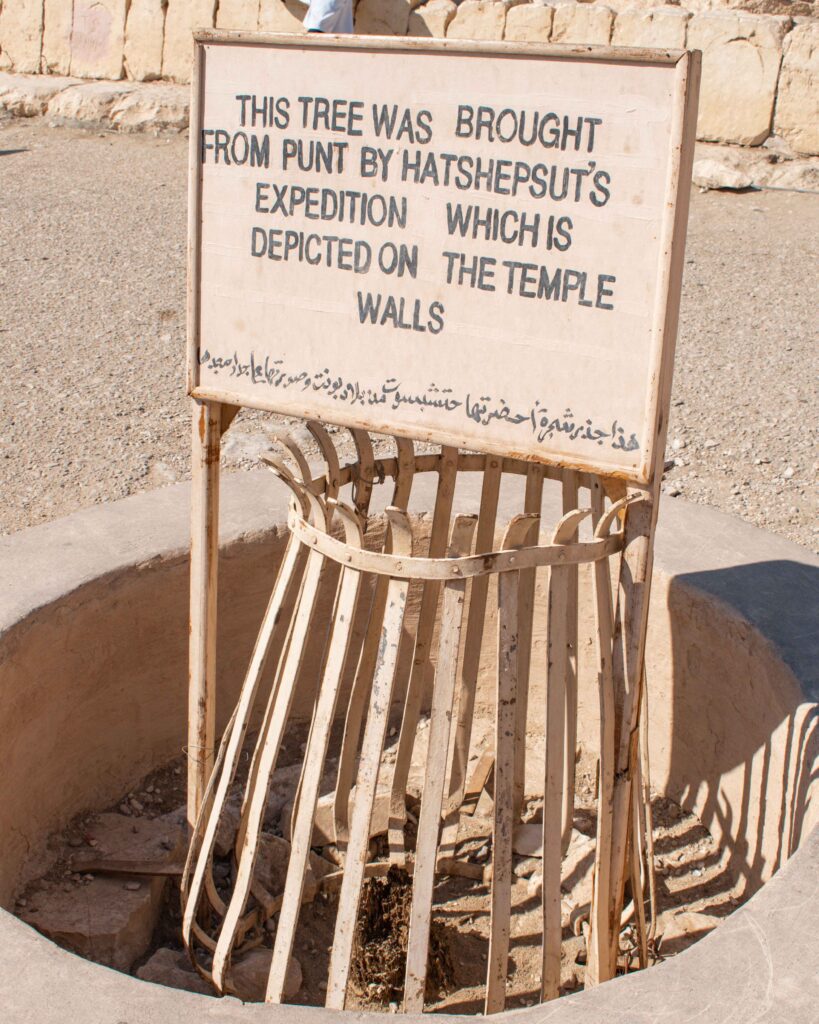

On the ground level, there was originally a garden with exotic trees gathered from Hatshepsut’s trade expeditions to the region. Although the garden is sadly no more, either side of the walkway are two dead tree stumps, thought to be the remnants of trees brought back from overseas. An avenue of sphinxes lined the route up to the temple.

On the second level, there are two main sets of reliefs. One depicting Hatshepsut’s immaculate conception with the god Amun, and a hypostyle hall with twelve Hathor-headed columns. The second set of reliefs are my favourite. They contain one of the first pictorial documentations of a trade expedition. Known as the Punt Colonnade, these remarkable scenes document the trade mission to Punt – thought to be modern day Somalia – to export produce such as cinnamon, gold, ivory and incense.

On the third level, there is a sanctuary to Amun, which was rebuilt in the Ptolemaic period.

COLOSSI OF MEMNON

Somewhat confusingly, this site has absolutely nothing to do with Memnon! In fact, it is really two huge stone statues of Pharaoh Amenhotep III. The 9th ruler of the 18th Dynasty, his reign was a period of considerable prosperity. Many regard it as the peak of Egypt’s artistic and international power.

The two statues were commissioned during Amenhotep’s 39 year reign, and show him in a seated position, looking eastward toward the river. Each is over 60 feet high and weighs an estimated 720 tons. The two smaller figures carved near his legs are of his wife Tiye and his mother Mutemwiya.

The statues originally stood at the entrance to Amenhotep’s mortuary temple, which would have been the largest complex in Egypt in its day, covering an estimated 86 acres. A series of earthquakes in 1200 BCE and 27 BCE destroyed most of the complex, leaving only the two huge colossi still standing today.

The Colossi get their name as result of a crack that emerged following the earthquake of AD 27. Over the following decade Greek travellers and historians reported hearing a whistle emerging from the statues at dawn. These early Greek travellers named the statues the Colossi of Memnon, as they associated the phenomenon with their own mythological hero, Menon. They believed the sound was the cry of Memnon greeting his mother Eos, the goddess of dawn. The fabled whistling came to an end in AD 196 when the crack and the statue were restored by Roman Emperor Septimius Severus seeking to curry favour with the oracle.

Unlike almost all of the other sites on the west bank of Luxor, the Colossi of Memnon is free and open 24 hours a day.

THE PRACTICAL STUFF

Costs – we visited all of these sites as part of our itinerary aboard the SS Sudan, and as this included a private guide and all transport, I think it offered us fantastic value. You can read more about my thoughts on whether a Nile cruise offers value for money here. Costs for individual entry are below (excluding photography tickets and extras):

- Luxor Temple – £160 EGP (£4/$5)

- Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple – £140 EGP (£3.50/$4.50)

- Philae Temple – £100 EGP (£2.50/$3.20)

- Edfu – £60 EGP (£1.50/$2)

- Kom Ombu – £80 EGP (£2/$2.50)

- Karnak Complex – £160 EGP (£4/$5)

- Valley of the Kings – £240 EGP (£6/$8)

- Valley of the Queens – £50 EGP (£1.30/$1.60)

- Tomb of Tutankhamen – £300 EGP (£7.60/$10)

- Tomb of Seti I – £60 EGP (£1.50/$2)

- Tomb of Nefertari – £1400 EGP (£35.50/$45)

Whilst these ticket prices on their own are amazingly reasonable to see some of the world’s greatest treasures, if you are visiting all of the temples and tombs, costs add up quite quickly. So if you plan on spending several days around Luxor and visiting several of the sites, I recommend buying a LUXOR PASS. The premium pass (US$100) includes the tombs of Seti I and Nefertari. The pass can be bought from the Department of Foreign Cultural Relations at the Ministry of Antiquities in Zamalek (Cairo) or from the Public Relations Office in the Luxor Inspectorate, behind the Luxor Museum on the east bank of Luxor. The office is open 9am to 3pm each day, Monday to Friday. You need to provide a photocopy of your passport and a passport photo.

Amenities – there were bathrooms at all of the temples and sites we visited. The bigger complexes (Karnak and the Valley of the Kings) had multiple bathrooms at different ends of the sites. There were also simple cafes, selling small snacks and beverages, at all sites.

Tipping – known as “backsheesh”, tipping is such standard practice in Egypt it is almost a part of the culture. Tipping 10% of your bill is standard at cafes and restaurants, whilst loose change is acceptable for street vendors. For smaller purchases, rounding up the bill or not asking for any change is appropriate. Note that the service charge on your bill goes to the establishment, not the waiter or waitress so you are expected to leave some cash on top.

It is also important to tip drivers and guides, but the amount is more complicated as comes down to service and quality. As a general rule, most we spoke to advised tipping a driver £50LE and a tour guide about £100 EGP for a full day tour. Most Nile cruises have a gratuity box, to allow you to leave a tip at the end for the entire crew, but it is worth checking if this includes the guides on your specific boat.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, when you first arrive in Egypt be sure to change a larger note into a handful of £5 EGP notes… you will need these to pay the attendant (and acquire toilet paper!) to use the bathrooms almost everywhere you visit.

Scams/“the guards” – unfortunately, Egypt has gained a reputation as a destination in which you have to always be on your guard for a scam. Whilst we had no problems during our trip, and never felt unsafe, we were grateful to our guides for preparing us to deal with the temple guards. As you walk around the temples expect to be approached by guards offering to show you the best photo spots, asking for your phone to take a photo of you, or offering you access to areas behind the ropes (a bad idea regardless if these amazing antiquities are to survive for another 4000 years!). Such helpfulness will immediately be followed by a request for payment. It was clear that this behaviour greatly annoyed, and even offended, our guides during our visit. They had all studied for many, many years to become expert in their subject matters (all had completed or were completing PhDs) and had all gone through rigorous testing to become licensed tour guides. They all told us they felt angry that made up information was being given, and that visitors were being pressured. All noted that the temple guards already receive a salary from the Ministry of Antiquities, and few knew much about the facts they purported to spout. We found a firm “no thanks/la shukran” to requests for photos, and a non-committal (“yes, it’s beautiful”!) response and walking away when information was offered meant we were not hassled as it was clear we were not going to be paying out. The poor souls who allowed themselves to be pulled into conversation quickly found themselves pressured to part with cash.

Be sure to also check out my reference guide to the Valley of the Kings and Queens, and my other guides to our wonderful Egyptian adventure.

Leave a Reply